Couriers in the Wind

Article written by Andrea Benesso for Al Vento Magazine, with the support of Selle Royal

Two young fish are swimming along, calm and carefree, when they meet an older fish coming from the opposite direction. He nods, greeting them with “He nods and says, ‘Morning, boys! How’s the water today?”

The two young fish swim on for a bit, until one looks at the other and asks, “Water? What’s water?”

This now-famous little parable, retold some years ago by David Foster Wallace, came to mind after a day spent riding through the city with the guys from Milano BiciCouriers. I had asked Andrea, one of the founders, for his opinion about traffic; his answer—more thoughtful and articulate than I’ll write here—made me think of that story exactly: “Traffic? What’s traffic?”

Not because cars, congestion, and noise don’t exist (they certainly do), or because couriers aren’t aware of them, but because after a day of pedaling with them, what struck me most was how much they seemed to belong to the current—the rhythm of traffic lights, the flow of cars, the pulse of the city itself—so much so that you can’t help but notice a kind of harmony. And to talk about harmony when speaking of traffic—which for me means only noise, smell, and danger—left me amazed.

Traffic is, unfortunately, part of the landscape. Yet those who ride dozens of kilometers every day, hauling hundreds of kilos, don’t ride cursing as I probably would; they ride as part of the flow: interacting with cars, pedestrians, and vans, letting everything move while skillfully avoiding danger.

It’s hard to explain, but watching Andrea rest his hand on a car or whistle to a driver made me think of a gaucho guiding cattle, or a surfer studying the waves. I didn’t witness a single moment of anger, and I went home imagining messengers as a kind of bicycling samurai.

Perhaps that’s a naïve simplification—after all, I was pedaling on a sunny day, only worried about not getting hit, and more or less mindlessly following Andrea—but that was the feeling: traffic as a current in which to flow until that promised day when traffic disappears forever. “Like during the lockdown,” as Alessio told me.

Inside the Life of Couriers

But back to the beginning. The idea of riding with the messengers and studying their philosophy—because that’s really what it is—by using one of their cargo bikes and following them from breakfast until the lights of the city turned on, came about because Selle Royal launched a project this year called Selle Royal Support Bike Couriers.

Support Bike Couriers connects couriers across Europe—from Copenhagen to Nantes, from Berlin to Brussels—offering them products, support, and visibility, highlighting their everyday lives and their role in society, which goes far beyond work.

Bike couriers stand on the front lines of sustainability, culture, and the movement toward more livable cities. The company’s “support” stems from a belief that the bicycle—more than 100 years on—is still a vehicle capable of change and improving people’s lives.

The BiciCouriers’ headquarters is a basement that serves as logistics hub, office, workshop, and locker room—one of those places that makes you think of Bianciardi’s working-class Milan, before and beyond fashion and design.

Their bikes, all Bullitts, are covered with stripes and stickers, like scars telling of a life where there’s no room for a glittery kind of cycling. This is where work happens: fast, efficient, and essential to keeping part of Milan’s economy running.

Each bike reflects its purpose—no frills—effective, quick, and maneuverable despite their size and easy to handle through cars and over tram tracks. The couriers treat them like John Wayne treated his horse, and every Bullitt tells a story, of which I only caught a glimpse.

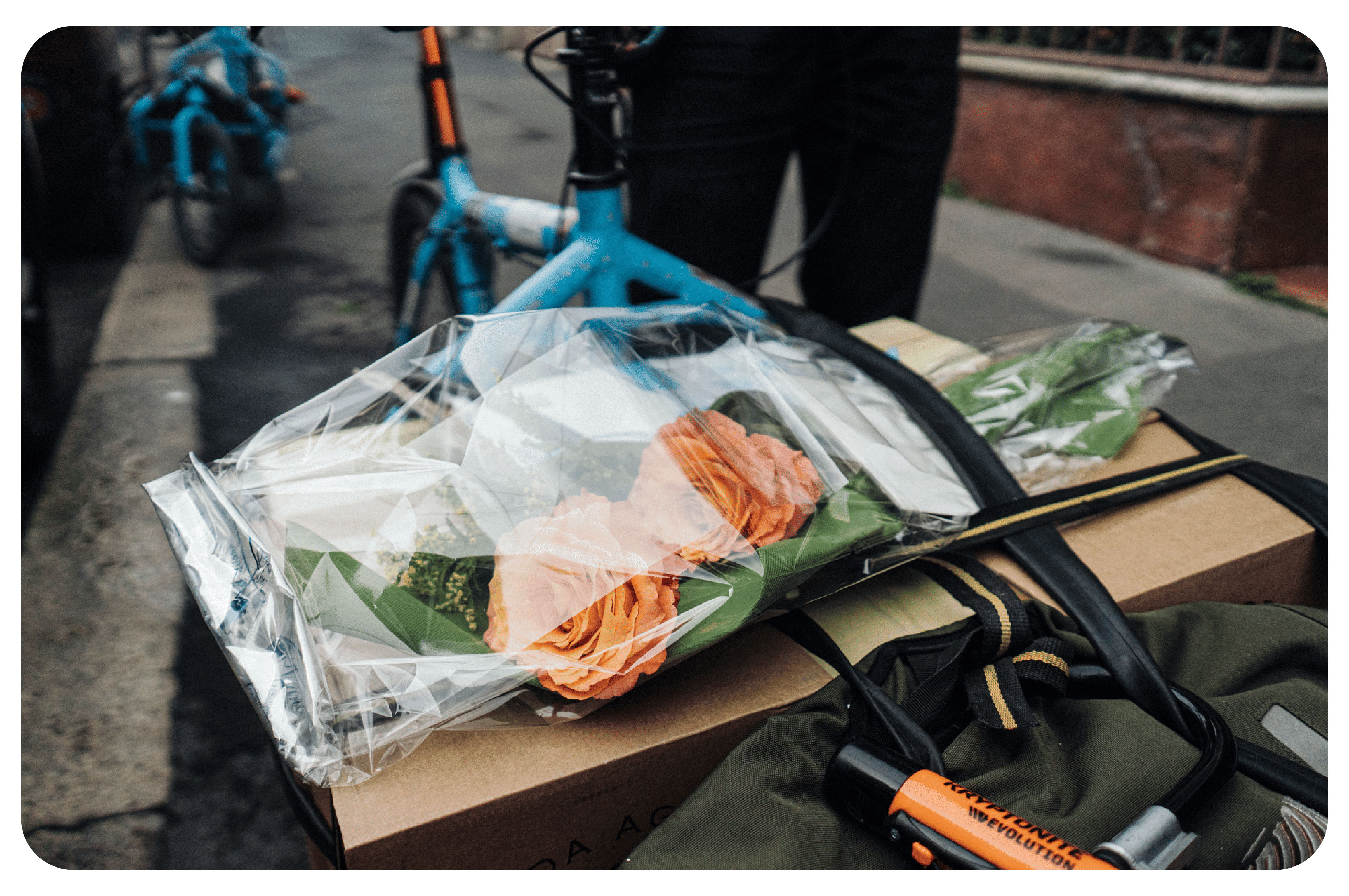

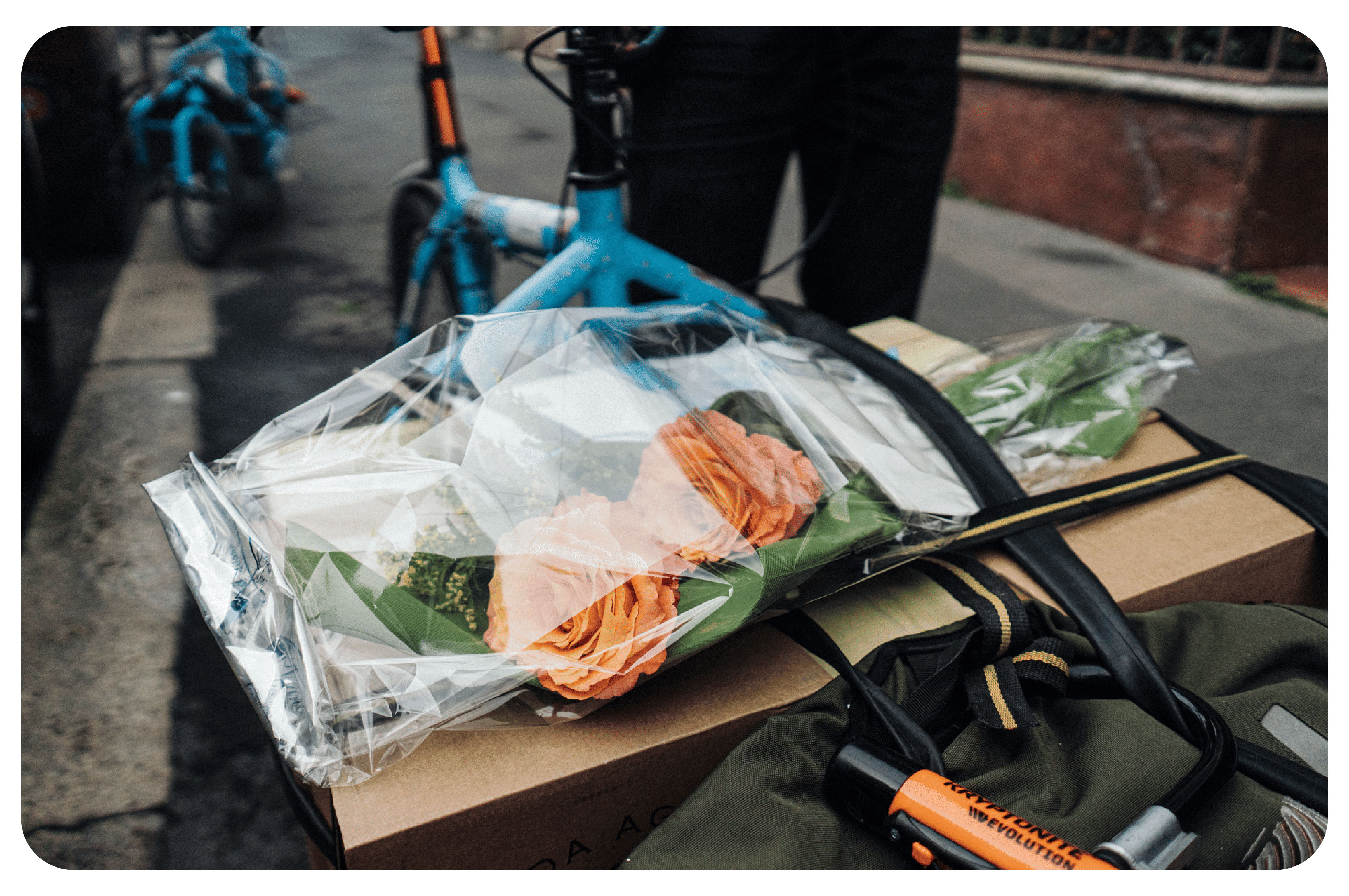

They’re racing bikes in spirit, but working bikes in form: carbon components, clipless pedals, but also comfortable saddles, straps for cargo, and theft-proof locks. On roundabouts, leaning into turns, Andrea pedals his loaded Bullitt hard, like a futuristic man-bicycle.

Their clients are varied: multinational companies wanting to look green, communication agencies and architects, hotels and B&Bs needing linens, restaurants needing wine or meat, and even lovers needing flowers.

Everything starts from the desks of Renzo and Alessio who plan each messenger’s route. The itineraries aren’t generated by an algorithm—each rider moves faster going his or her own way as they know the city better. Every shortcut, traffic light, or bike lane counts on days when both kilometers and kilos pile up. The rhythm is constant, dictated by Milan’s most famous saying: no time to waste.

Following Andrea or Alessio through intersections means trusting their almost millimetric knowledge of the streets as well as the tempo they ride: they move a split second before the light turns green, know exactly where cars will pass from the opposite direction, and read the flow ahead as if they were seeing the code in The Matrix. Not a single pedal stroke is wasted.

A Different Milan and the Heart of Couriers

The 15 messengers are all young and sharp as blades. “This is a job you do for the sense of belonging it creates,” Alessio told me. “Being a messenger isn’t easy, but it’s like being part of a family—both in Milan and across Europe. We meet to ride, to race, to spend time together. It’s a world that’s hard to leave.”

Andrea, one of the founders, has been delivering by bike for over ten years; he rides between 70 and 100 km every day, sometimes carrying 400 or 500 kg of goods. The yearly total adds up to around 45 tons—if not more.

By the end of the year, including weekends (when he still rides, without having to deliver anything), he’s covering more than 15,000 km. For the customer, the courier appears only at the beginning and the end—the pickup and the delivery—always with a smile and the air of someone who doesn’t have time to waste.

In between lies Milan: its rough streets and shop windows. Sun or rain—it doesn’t matter. Here, you ride.

Cars, vans, even scooters can’t keep pace. In the city, it quickly becomes clear that the bicycle is the most efficient machine—no parking hassles, no circling the block, just the freedom to stop at any doorway, slip through bike lanes, and glide across the restricted zones of the center.

Beyond the postcard Milan of the cathedral, fashion boutiques, and Lombard Art Nouveau villas lies another, more horizontal city: stretches of social housing, supermarkets, warehouses, workshops, murals, gas stations, ATMs, and pizzerias.

Along these unremarkable routes, you discover a different Milan—sometimes shadowy, sometimes radiant—where bicycles flash by like the horses of Native riders, who, in the end, we can’t help liking a little more than those of John Wayne.